This is a companion piece to the Samson Isaan Muay Thai Library session which can be seen in its entirety as a patron supporter. You can support this archivist documentary project by becoming a patron (suggested pledge $5). A free 3 minute YouTube clip is above.

The Two Muay Thais of Thailand

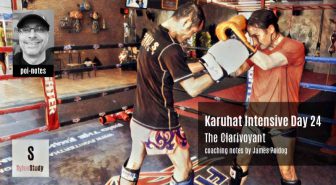

A chain link fence makes up the outer wall of the gym, like that of a school playground, the kind of which I used to play on as a kid, or like an MMA cage of today painted black. The soot-gray of the metal, a tinniness you could almost taste is missing, as is the high-tone chime that would come when it shook, when a stray ball from the grounds would make it ring. But the infinite stack of triangles is still there, the inside and outside of it, how you could see straight through but were still bound, the way it tricked the eyes to thinking they were not still enclosed. That high, semi-transparent wall of firm metal link is at my back, and I’m watching Karuhat Sor. Supawan move through his permutations with the regularity and varied genius of Bach. It’s been a month of more or less coming to this gym every day, and meeting the man who earned the name “Yodsian”, great guru, top master, ultimate yogi, wizard in the woods, the potential translations feel endless. He is a ribbon in the ring, a shiny, satiny thin ribbon that twists with the turn of a hand reflecting differing light from every angle. He holds a mirthful smile at almost all times as he ballroom dances my wife Sylvie through a steady cadence of 123, 123, 123, teaching her to dance. These are not technical moves, not do this, then do this. This is pushing down into the music, the music of fighting. Nobody can really teach this, other than those who have felt it – and there are a lot of wonderful things that can be taught by many men and women – its the music beneath the code, its the Source Code, and you could spend an eternity staring at it and not know what it means.

It’s a remarkable moment, out here at the edge of Bangkok. Chatchai Sasakul, one of the great western boxers in the history of Thailand, and perhaps it’s greatest boxing coach, moved his gym from the middle of Bangkok’s Ramkhaemhaeng commercial district to the far North of the city near Rangsit. It sits at the edge of a great and open lot that 3 times a week hosts an enormous market in the evenings full of stalls, and mats strewn with wares, and wandering families. In the day, and all other times, it’s just a cement savanna across which dog packs trend toward movement, or signs of other dogs, and lone dogs keep to their own company under awnings or overhangs as if in a post-Apocalyptic film. Inside the gym is well-appointed, beautiful. Outside the sunlight blares. With Karuhat dancing and shifting in his soft-shoe Muay Thai, it is an oasis cut across time. We feel like we are “way out here”, on a beach somewhere, the oceans of water, time-water, washed from the 1990s when Bangkok was blasting with the greatest Muay Thai that ever lived, and we are rafted in this gym, on it’s great cement wasteland, Karuhat dictating the truth to his ever-faithful, and ever frustrated scribe. And I am filming all of it, because I don’t want to miss it, we don’t want to miss any of this. These are the wisps that get lots forever, that never come back. The wisps that make the life of what happened back then when big mafia bosses were banging against each other with their champions, and the boys of Isaan rose up to fighting heights far above their villages, coming to possess incantational powers captured in their styles.

The moment is this. A bright, fuchsia pink taxicab rolls up right next to the black chain link wall, parking half-way in the shade of it, and stops. We are out here on our island on the cement, our cloistered new-gym of shiny mats, and hanging bags that have not started to bow or split, and Samson Isaan arrives. Out of the driver’s door steps a big smile, and I’m sure that heavy amulets were dully tickering in his shirt – I don’t know this to be a fact, but he felt like that kind of man. He’s barrel chested, his eyes were twinkling. He’s not physically large so much as radiating with a powerful manna. He doesn’t really know where he is, in the sense that it’s an entirely new space to him, or even completely why he is here. But it’s his cab and he can go anywhere he likes.

The gym is completely empty but for us, and Karuhat after a brief hello just continues on with this 123,123,123, transcribing his greatness into the reflexes and perceptions of his scribe. Samson Isaan – and his fight name means what it sounds like, maybe something like “Strongman of the Farmland” – wanders through the big gym space looking at what Chatchai has done for himself. It’s just us. Two farang with a camera, and two great fighters of an era.

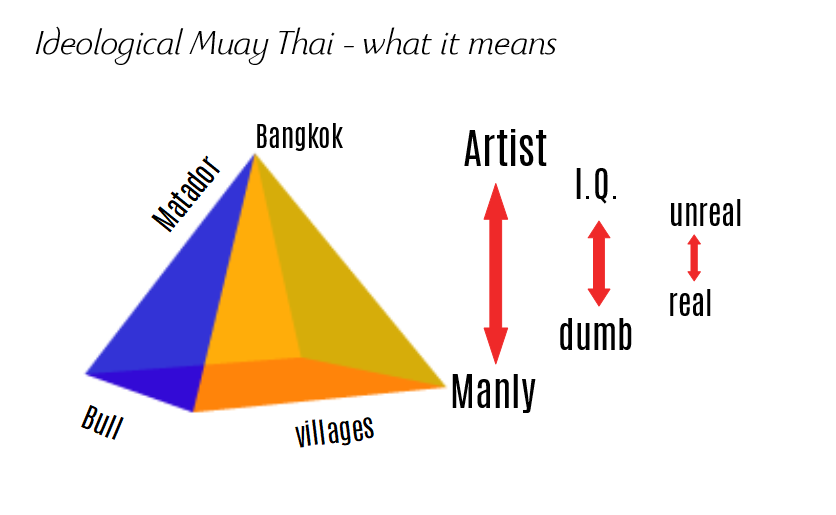

By the time Sylvie is training with Samson nearly half an hour has passed. She’s just come off of more than an hour with one of the more silky fighters of his generation, to now training with its strongman, Fighter of the Year in 1991. Now, there is a basic divide in the art and sport of Muay Thai in Thailand. On one side are the “artful” fighters (muay femeu), and on the other side are the “power” fighters (this goes by many names: muay khao, muay buk, muay mat). Artful fighters, like Karuhat, look down upon the more brutishly styled fighters of the Muay Khao class, with a kind of wrinkling of the nose. Muay Khao fighters like Samson look down (from below) upon the prissyness of artful fighters. In the ring they are essentially bull and matador. Sometimes the bull wins, and if he wins a lot can be much praised, but always the matador is protagonist, the hero. Very complex relations between fighting styles and techniques become cartooned in this over-simplificaiton that honestly has strong class associations. Bulls, in the stereotype, come from rural Thailand, the 1000s of villages that cover its agricultural and economic womb. Matadors also come from rural Isaan, but their artfulness expresses a liberty from their roots. There stands in the center of Thailand a beacon of royal ascension. This was expressed, for Muay Thai, at the heights of the National Stadia (Lumpinee, Rajadamnern). For fighters converging on this center to win and dominate in these stadia was to, in a certain sense, transcend. The artful, femeu fighter represents and expresses a kind of ascension, taking the most brute of human action, The Fight, and raising it up to a glorious form, and to do so artfully. This involves taking all things base, and elevating them. The instincts become purified and refined in techniques. The emotions recoded into moments of control, and displays of careful ardor. This is, Muay Thai is, a kind of social alchemy, and the Bull Fighter, even undefeatable ones, lie closer to Lead than Gold, in this pyramid of esteem.

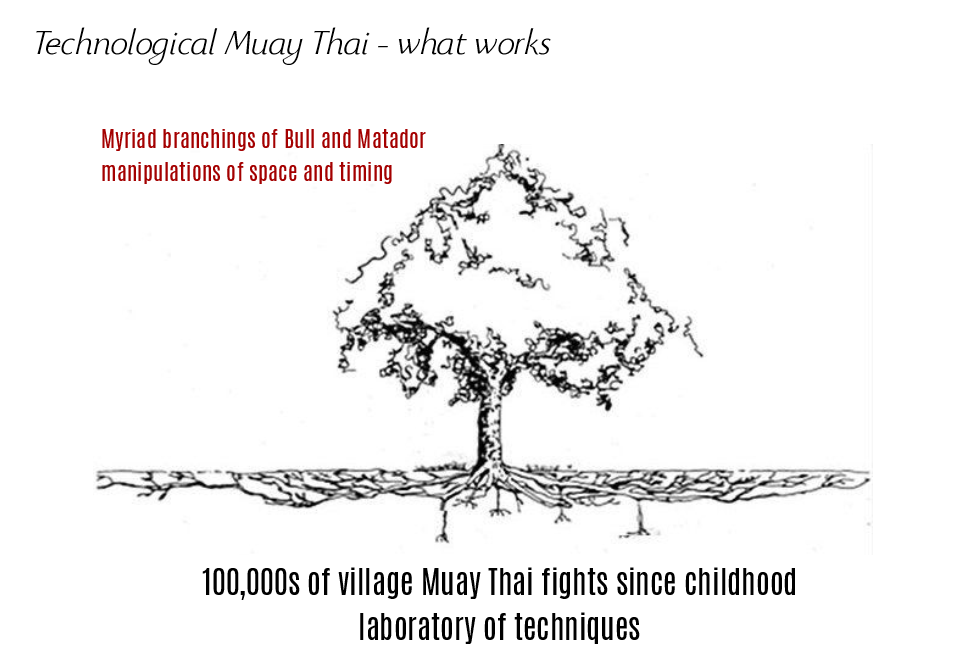

But, in the anthropological sense, if one is to appreciate Muay Thai as a language – let’s say – and a practice, in order to strip away as much of the ideological as possible, the techniques of femeu fighters, great historic fighters, did not come from Bangkok itself. It’s not that Bangkok, as if a great OZ, held the treasured keys of how to become a Matador. The Land of Muay Thai, the 1000s of villages where endless laboratory fights churn for generations, like a mad AI self-learning through iterations, this is where techniques are born and die. Bangkok is but the flower of those roots. And what is obscured by the ideological cartoon of high and low, is that Bull has many techniques, and is in fact quite artful. It is not that there is the Art of the Matador, and the Heart of the Bull. The Bull is a magician in his own right. He plays with the magic of the illusion of strength. He dallies with space and time, no less than the Matador, a matador like Karuhat. And this piece is about one small part of that. The Pulse.

After the session Karuhat, one of the Princes of Muay Thai history, would make fun of Samson’s style and techniques, in fact, during the session they each would make fun of each other. Samson would laugh in his bellicose, infectious wide-toothed grin about how he would never dance off a 5th round as a Nancy-boy like Karuhat might, Karuhat would imitate Samson’s knuckles-to-the-forehead punching style, as if it were a Caveman’s. We are talking about some of the greatest who ever fought deriding each other in absolute jocularity. What I want to capture in this moment is that cutting across all technique, the vast reservoir of fighting experience and knowledge, is this divide that splits everything into higher and lower. And the fact that there is likely no difference in the density of technique in the higher or lower forms. This high/low permeates all techniques, and the hearts of all fighters. Dieselnoi, remembered as greatest Muay Thai knee fighter ever (and thus ever in the danger of being classified as a Bull, a fighter who expresses only incredible heart or power) is very insistent that the knee and clinch fighters of today lack technique, that they are dumbed down versions, while in the same breath laughing that Samart, a fighter often thought of as the Prince of Princes, “hit like a girl”. If we are to see into the techniques and arts of Muay Thai in Thailand, we have to gasp with two hands. In the left we hold the ideological pyramid of ascension, in which any particular fighter is escaping the brutality of his origins, through technique, placing the Matador above the Bull, a position that is ever threatened to be shown as unreal, over-refined, and un-manly, and in the right hand we hold all the techniques, realizing that high level power fighting is brimmed with techniques, their own dark art of control over space and timing. Because fighters fight along these two planes – what something means, and what something does – high level fighters on both sides of the divide have come from lineages knowledge that operate through the conversation of both. Ultimately, in the eyes of the judges, the Muay Khao fighter is working on the ideological plane to assert the positive half of the binaries he suffers from. This takes technique. Techniques of the heart and mind, and of also of the body, no less than any other assertion on that plane. Herein lies the art.

All this is to say: the Bulls know what the fuck they are doing. There was a particularity of standing in that gym, cut off from so much of what is Muay Thai in Bangkok, with two absolute legends who themselves live at the periphery of the the Sport they once reigned in. Karuhat has no gym, he is an itinerant wizard who lives his old gunslinger life through a cadre of friends from the glory days, a circle of generational badassness, of which Samson is a part. These older legends are (almost) all friends now. Samson cheerfully drives his taxi. He is in no gym. He recently beat the once feared Weerpol in an Old-Timers throwback match at Lumpinee, which is the fashion today, as Muay Thai sees its devoted demographic aging, and longing to see the faces of those they adulated in their youth. One could not help but feel, as Samson joked with Sylvie, asking: “You trained with Karuhat, it’s different with me” (paraphrased), broad-grinned, that we were sitting in a vortex of technique, of men…and of time. I’m captured by the idea that the Bull has his own magic, that the Bull allows the Matador to think that he has no technique.

Dictating Space and Tempo – The Art of the Bull

While the Matador wants to give the illusion that he is orchestrating his opponent, pulling strings, waving his hand to the instrument hearts of the crowd, letting things play out with the “pause” or “delay” perhaps his greatest signature weapon, the Bull uses tempo. While the Matador want to create accents and redirections in order to lay the foundation for dramatic narrative moments, framing positions where an exchange, a round or even an entire fight can be overwritten by a gesture, the Bull builds a powerful frame of tempo itself. In Samson’s case he is driving a hard and powerful baseline, one that is designed to over-sum any play the Matador attempt. This is not just shouting over softer voices. This is systematic and technically adept disruption. No less disrupting than stinging jabs, or off-beat and delayed striking. This is creating a firm and fixed tempo upon which all variation must bend. If you watch the full-session with Samson you can see it. There is veritable glee in his technique. He relishes its efficacy, no less than a maestro with a paintbrush hair might turn the edge of a rising microscopic oil paint dollop. This pleasure, is the pleasure of an artist. The one who creates.

Ultimately, a fight is a battle of tempos in which the tempoless fighter is lost. This is one of the beautiful, an irreplaceable things about the Muay Thai Library project, one can see tempo being taught in almost every session. Normally you can only find tempo by watching fight video, but you seldom can see it taught in the way that a music is taught, or a language. By letting the camera run for an hour or more you can see the instruction of tempo unfold. Yes, there may be techniques being shown, but their meaning and efficacy are buried in the fighting tempo, and the tempo itself is an expression of the fighter’s character, their Being. This is why Andy Thomson told us years ago: “There is not one Muay Thai, there are thousands. Each person has their own Muay Thai.” And this is, in part, why fighting (and not just practice) is an intimate part of the art itself, because the pressures of fighting – its fear, pain, and humiliation – are essential for bringing forth character, the quality and kind, which then expresses itself in The Real of the tempo of a style. When you watch legends like these teach you are seeing a tempo forged in fires, something that is irreplaceable. I’m still taken by the surge of heart, which some call thymos, I felt when filming these techniques, especially Samson’s Pulse. Standing there I could feel myself swept up by the beat of it, the fast undulations, no less than if it were pounding base in the heart of a big speaker. It’s a drum beat, and it goes right to Samson’s heart and character, his smile. It’s a technique of heart, but no less a technique, in that it systematically steers both time and space, and imposes itself, aesthetically, on viewers. It has hand positions, variations of attack and defense, a body posture, and a natural cadence. It is style no less than Samart’s lazy-boy side teep, just of a different tempo and rhythm. Think thrash metal rhythms, think Baroque intensities.

In the session, if you watch it in its entirety, Samson extols the use of disruption. At one one, in answer to how he liked to fight punchers (muay mat), he laughs about how intermittent jabs will snap the head back and keep them from starting their stack (a term Sylvie and I use following the analysis of Greg Jackson (http://8limbs.us/muay-thai-thailand/lessons-rousey-grappling-stacks-and-sylvies-muay-thai-clinch-game)). What is key is that Samson is thinking, technically, about disruption as a main tool. Samson’s Pulse, part of a kind of Juggernaut attack, is a close-range, space dictating attack which principals disruption. And it is beautiful.

Vibrational Muay Thai

Here’s his internal tempo, expressed in a non-technical form. This is the metronome of his heart, what he’s feeling when he’s using the Juggernaut pulse:

And here he is laughing with Karuhat (off camera) who he knows thinks not much of his style, reveling in his forward “dern”, traditional Muay Khao rhythms, just churning up the space in front of him. The joy of it, the Bull of it, almost celebrating the “simple man”, the farmer of rural Isaan. This is technique, a close and systematic dissolving of opponent opportunity, the elimination of flourish.

And here below you can read the rhythm, as Sylvie reaches to express it. Yes, you can see it a bit in her, but you can really see it in how he holds back his own pulsing, allowing her imitation to push forward. He absorbs and receives it, when in a fight he would rhythm up against what she is doing, and impose his own answering tempo. There is really something beautiful here for me. I can feel him beating forward even as he silences himself, it’s like unheard notes of music that a musician might not play, or an unused rhyme from a poet, forcing you to hear them nonetheless. He’s laughing at the start of this GIF because Sylvie just told him how beautiful this forward-pressing technique is, something I’m sure he has probably never heard in his life.

It’s part of a whole system of attack and defense (in the full session you can see the range of his use of elbows), some of which you can see below – he was a Thai boxing champion and his use of uppercuts, hooks and crosses fit in this close-quarters style. In this GIF below he is not only displaying his own variety of weapons and rhythm in his press guard, but he is also inviting Sylvie to counter fight on beat in the same pulse guard he is teaching. He experiences these are battling tempos, in conversation.

But I don’t want to lose track of the under-music of the whole. Whether he is fighting another close-range opponent, or a more artful Matador, it is this under-music of a disruptive, space-eating tempo that grounds his efficacy, itself an expression of his character. The entire system is built up through the Muay Khao marching rhythm and control of space/time. And more technically, what is particularly beautiful is that from Southpaw it exploits the natural advantages of mixed stance opposition. Because the power side is shared, this means that the fight can be localized just to one half of the body much of the time. This is well recognized in distance Southpaw fighters who like to kick for instance. Many Thai Southpaws are big left kickers, blasting through the open side of Orthodox fighters. But at close quarters this shared power alley becomes even more extreme. Pulsing through and against your Orthodox opponent really deprives them of almost any Close Side attack other than elbows and an occasional uppercut. The lead hand helmeted guard takes much of that away. It then becomes an Open Side war, which which Samson’s uppercuts, crosses and rear elbows become quite dangerous. The pulsing rhythm is constantly dis-balancing the timing of the opponent, while power hand weapons repeat themselves with variations on a theme. It is a Baroque battering ram.

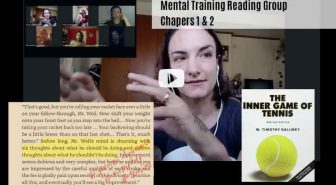

Sylvie’s Take on The Juggernaut

Above is Sylvie’s take on what Samson was teaching her, and what she’s taken with her as a fighter, in a quick one minute vlog. She’s calling this technique The Juggernaut, maybe for obvious reasons. In it Samson is employing classic Muay Khao rhythms and dern energy, but what makes The Juggernaut interesting is how it uses very close proximity with that tempo. The hand is high up on the forehead (from the Southpaw stance), so the forearm and deep chin tuck defends against the lead hand of the Orthodox fighter. The palms are to the skull, not turned out as some Muay Khao longer positions assume, and the forearm literally bangs into the lead side of the Orthodox opponent. Fighting at very close range like this, without collapsing into clinch, can put your opponent at a disadvantage if they aren’t used it it. Fight where you are comfortable and others are not. For Sylvie this kind of head-banging attack can lead to open side knees and of balances, and eventually could develop into the kinds of power side boxing attacks Samson used.

Continuity and Rhythms

At the end of the session and after Samson left the ideological components of Muay Thai took over. Karuhat, the deft manipulator of space, consummate narrator of dramatic moments, laughed with Samson over his He-man style, and Samson shook off Karuhat’s fancy-boy pedantry. Karuhat the next day joked about how easy it would be to fight Samson (remember Samson had just beaten Weerapol in an Old Man match), making him suddenly trip, as if he were falling over his own feet, and I’m sure that Samson felt like he could just walk and tempo through the paper tiger of Karuhat’s art. These are two boys from Isaan, Samson from Roi Et, Karuhat from Khon Kaen, playing on opposite sides of the fence, but artists in every way.

It’s another morning and Sylvie is opposite Karuhat who is working with her on continuity. The coffee is starting to take effect for me, and I am leaning into the ropes of the ring steadying the camera as best as I can. The hypnotic elements of Karuhat’s Muay Thai can lull you in their grace. — You can read our vlogged thoughts on Continuity here,and my more philosophical thoughts on it here. This could be any morning of our 30 sessions we filmed together, attempting to capture the innerworkings of one of the most praised stylists of the Golden Age. You can watch over 25 hours of footage and commentary here. — Karuhat is almost on skates in these sessions. They are sleepy and relaxed, and in a very real way he is trying to transfer this relaxed, sloping energy to Sylvie, get her to see it, to feel it. For over 40 hours she swam in those warmer waters, adding its perceptions to her advancing Muay Khao style. What watching Samson and Karuhat in the same space did for us I think was to emphasize just how much of fighting is tempo. Karuhat slows things down, dissipates, so he can create a visual change of direction or intensity. He is looking for punctuation. He is taking away space by taking away angles, and by focusing on the open side. Much of this website is devoted to his lessons in space contraction. He delays, in order to accelerate. A Muay Khao, or Muay Dern fighter like Samson is a vibrational fighter. He is insisting on vibration to shake things loose. He creates openings, not only by imposing fatigue, but by repeatedly contracting space into a compression of time. One of the most interesting things about his style, something that Weerapol discovered, is that while he compresses everything, he had an incredibly long cross. I’ve never seen a cross that extends like his. It may have been his secret weapon, in the sense of how much unexpected distance it could travel. You can see it below. He had long arms, but he also achieves great extension with his hip and shoulder rotation. Out of his pulsating crouch he could reach out and touch you with power at distance (below). What the rumination on Samson Isaan impresses on me is that all styles are manipulations of time and space, this is what makes them techniques. Without the context of distance and timing, they are nearly meaningless.

Tempos create expectations for the pattern-seeking mind, expectations that you can deceptively diverge from, but they also reach out and dominate the music of the other. This is what military analyst and philosopher John Boyd called “getting inside someone’s OODA loop”, which is essentially making your opponent re-active. What Samson Isaan’s pulse is about is getting inside the perceptive and adaptive loop of an opponent, through up-tempo cadence. It’s using the same boxer’s “busy fighter” tempos we know in the west, but at close, pulsing range, and doing so as a power fighter known and celebrated for his strength. People think of power fighters as using big-gun tools like explosive hands, or thunderous kicks, but Samson makes use of the classic Muay Khao vibration as a set up, disruptive tool, the grounds for his power. Great match ups, ultimately, are clashes of music. Seeing which music will prevail against which. The techniques of high level Muay Khao fighting are equal in art to the more celebrated Muay Femeu to the degree that they commit warfare on both Time and Space.

Snuffing Distance Against a Puncher

above, full fight, watch Samson work against a powerful, adept puncher. He starts in Orthodox stance so he can use his knee on Dor’s Southpaw open side. Then he switches back to Southpaw, Southpaw vs Southpaw. His Juggernaught helmet does not have the same natural resting place as it would against an Orthodox opponent, but he still manages to unleash his rear elbow.

Exploiting the Power Alley

above, watch Samson’s famous 2nd round vs the very dangerous Lumpinee champion Weerapol (who would go onto become WBC world boxing champion for many years). Early in the fight he is already in “dern” mode, pulsing forward, until he is able to land his big right hand down the power alley he shares with an Orthodox opponent.

Pulsing with Dern Into Clinch

above, watch Samson’s Round 4 march against Lakhin Wasantasit. It starts with pulsing openside attacks, especially with knees, which is then pressed in clinch. It’s the high tempo rhythm that pervades throughout.

If you are not a patron supporter yet you can easily join. The full session with Samson with Sylvie’s commentary can be seen here.

Filming this session and then editing it for the Library was personally moving to me. This is what I wrote on Instagram

“I just got through putting together and burning the Samson Isaan session which should be up soon – hopefully it will upload by tomorrow when we hit the road for Sylvie’s fight – but I’m going to tell you that it has a bid for my favorite session of all time. This is just my personal feeling, and there are already so many personal, wonderful sessions in the project so far, but this session is what the Library is all about. Not only is it full of Samson’s personal style – a Muay Khao, Muay Buk, Muay Dern power style that is seldom taught or examined, but Samson Isaan is a god damn (excuse my language) taxi driver in Bangkok. He rolls up to the gym in his taxi, is a little confused about what we are asking him to do, and just ends up having so much fun just showing his style and getting into Fight Space. Part of this Library is about not just capturing the techniques, but also the men, and he just fills me with joy. The session blows me away. I’m smiling right now, 20 minutes after having turned it off to burn it. The Muay Khao/Dern/Buk style is not esteemed, it’s not beautiful. This man is a taxi driver, and this is some of the most beautiful Muay Thai capture I’ve experienced.

Thank you to all the patrons, and the sponsors of this documentary project SMAC, Chikara Martial Arts and J Su & Family for making this stuff happen. That this video exists is because of you. And because of you people 20, 30, 40 years ago will know something about Samson’s style, and his incredible joy, that otherwise could not be known. This is what this project is about.”

These kinds of session in particular are what make the Muay Thai Library like no other. Samson Isaan’s techniques are ready to disappear from Thailand. He’s a taxi driver, he has no students, he’s no longer in Muay Thai, per se. But, as you can tell from the video it is alive and thriving in him. Documenting his technique as he would teach it is a big part of the effort of the Muay Thai Library. You can see the nearly 50 hours already documented in the Library so far, many of these krus & ex-fighters, some of them very great fighters, leaving no permanent record of their muay other than a few fight videos. When you pledge on patron, you not only can study their techniques, but you help ensure that they will be preserved for posterity.

You can directly support the krus & ex-fighters filmed in this project by donating to the Kru Fund (PayPal – sylvie@8limbs.us), funds to be divided between all filmed krus & ex-fighters, or to Samson Isaan himself – just write “For Samson Isaan” in the PayPal transfer.

You can follow my near-philosophical thoughts on Instagram or read my Sylvie Study Training Notes.